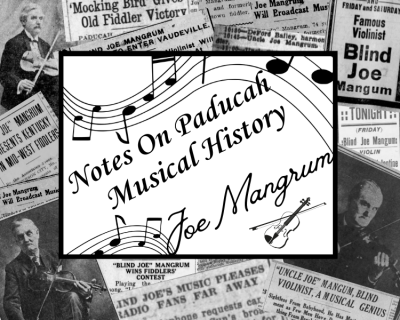

Joe Mangrum was an early star of the Grand Ole Opry and one of the most notable old time fiddlers to come out of West Kentucky. - Nathan Lynn, Local and Family History

Today we remember the late west Kentuckian Joe Mangrum (March 29, 1856 – January 13, 1932), born on this day. One of the area's most well-known musicians in the early 20th century, Mangrum played before the Chicago Civic Opera, campaigned with Tennessee Governor Robert Taylor, was a friend of humorist Irvin S. Cobb, and an early star of the Grand Ole Opry.1

Joseph Mangrum was born in Dresden, Weakly County, TN, to James and Catherine Husted Mangrum. James was a carpenter and a former Union soldier, serving as 2nd Sergeant 6th Regiment, Company M, Tennessee Calvary during the American Civil War, and twice a Prisoner of War.

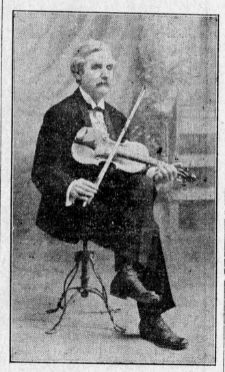

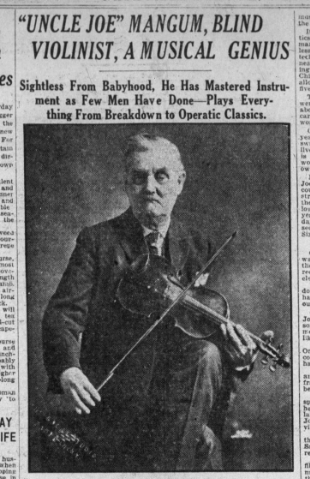

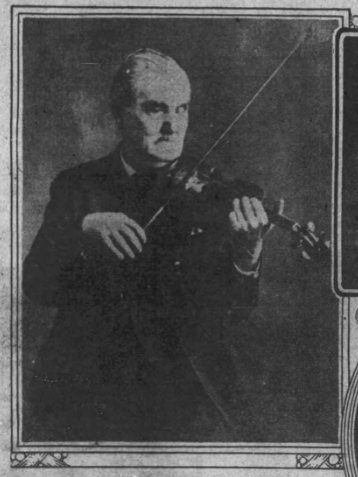

Joe spent his early life playing the violin in west Tennessee and west Kentucky. He began to show up in newspapers across the region and Southern IL and was referred to as one of the best fiddlers in the state, as early as 1885. Over the years he would be billed as Professor Joe Mangrum (Mangum), Blind Joe Mangrum, and Uncle Joe Mangrum. An article in the 1907 Fulton Leader called him “Wizard of the Violin.” 2

“I learned how to play a violin before I left Dresden, Tenn., when I was a boy. It was kind of natural like with tunes always in my mind. I never had a music lesson,” Joe noted in a 1930 Nashville Banner interview.3

It was said that at one time Mangrum knew over 5,000 compositions by memory. According to his obituary, “He lost his sight when six weeks old. Playing the violin came to him almost naturally, and at 12 he was an accomplished musician. He never took a music lesson, but the classics were as familiar to him as the song of the day. 'I remember the first piece I learned to play,’ he said one day. ‘It was “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing.” I learned to play, “Listen to the Mocking Bird” by following a mockingbird across the square at Dresden.’“4

From a young age, Joe’s musical interest seemed to span from folk to classical music. The Nasville Banner reported, “He has committed choice selections for practically all of the old masters to memory. In demonstrating his versatility, he plays a selection from Verdi’s ‘Il Trovatore’ taking in ‘Miserere’. Then beautiful bits from Wagner and Schubert. He knows them all. He stops suddenly, shifts his old violin under his chin and starts playing one of the latest blues hits. The strings vibrate in mourning tones. Now his arm moves in short even strokes. He plays ‘Rabbit in the Pea Patch.’”

The 1891 Memphis Commercial Appeal stated, “Joe is a genius in the fullest sense of the word. Born blind, he inherits a passion for music, and under his deft touch all manner of instruments yield their sweetest strains. Mr. Mangrum is a well-known figure in west Tennessee and the Kentucky ‘gourchore,’ and wherever he goes he has friends and is at home.” Newspaper reports like these in the late part of the 19th century led readers to believe that Joe was a more classical violinist than an old-time fiddler. But Joe’s palette was vast, and music was his language. 5

Joe amazed people from across the South and Midwest with his relentless performance schedule and became a recognized artist in numerous cultural avenues. He supported Tennessee Governor Robert Taylor by playing fiddle at the Governor’s notorious political rallies. Critics from the north, astonished by his skills and “unusual technique,” arranged for a special hearing before the Chicago Civic Opera Company. In 1910, Joe appeared in Annie Somer Gilchrist’s book The Night-rider's Daughter as himself, visiting the Lakeside Inn near Reelfoot Lake. His reputation had surely preceded itself. 6

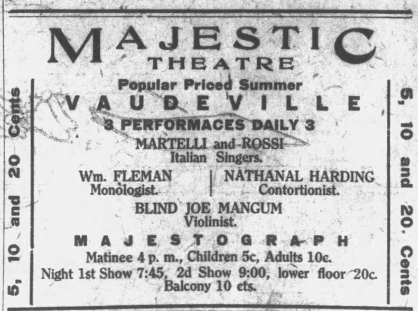

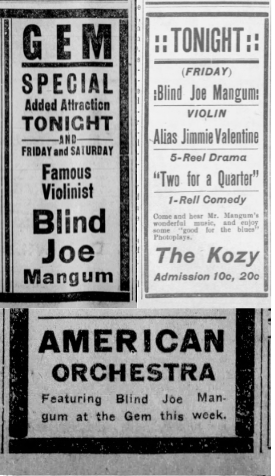

Mangrum spent stints living in many places including Dresden, Jackson, Martin, Memphis and Nashville, TN, as well as, Paducah, Hickman, and Mayfield, KY and Cairo, IL, often performing for extended dates. By 1909 it was reported that Mangrum was making $200 a week on the vaudeville circuit, being booked out of Chicago. The Montgomery Advertiser noted, “Unable to read a note, he can play anything he has ever heard upon the violin and his touch and tone is that of the true artist. The most difficult of opera selections is simple for the blind wonder and his own compositions have found favor wherever they have been heard.”

From 1913 - 1915 Mangrum found steady work performing at the theaters in Paducah, both solo and with the 20th Century Orchestra, in support of Vitagraph silent film screenings. He also performed at numerous hotels where he would often perform for extended periods of time. And in 1918, he volunteered his musical talents to the American Red Cross. At the age of 60, he married Mary Elizabeth Stringer, who was 25 years younger, in October of 1915 in Paducah.7

With the growing trend of radio in the early 1920s, Joe found a new outlet for his music. The Paducah Sun wrote of receiving letters, from places like Smith, AR and Slater, Iowa, from fans who loved hearing Joe on WIAR radio station. After years of touring the region and his newly found stardom through radio, Mangrum’s career seemed to start seeing more recognition. On January 13, 1926, he was awarded the highest rating at the Paducah Henry Ford “Old Fiddlers” Contest which would send him to Louisville to compete at the state level. He was recognized for his rendition of “Mockingbird,” beating out his young friend Rube Elrod, from Kevil, KY. The same week, Joe received an invitation to perform on the radio in Nashville, but it would be another couple of years before he would join the rising music city. Newspapers from Delaware to the Dakotas reported on the Paducah contest winner, spreading the notoriety of the region’s music. 8

While the commercialization of country and old-time fiddle music would propel Joe into the musical spotlight, he could not escape his love for classical music. This was said to have caused differing opinions between him and Grand Ole Opry founder George D. Hay. Independent Grand Ole Opry historian Byron Fayfare wrote, “When the Opry started, there were about a dozen fiddle players, but over a short period of time, that number was cut to 4.” Joe remained, along with Uncle Jimmy Thompson, the latter being more favorable to the likings of old-time and country fiddling. It’s at least ironic that Blind Joe Mangrum was long-mentioned with the terms, “old oprey,” and, “grand opera,” at the same time George D. Hay coined the term, “Grand Old Opry.”9

Country music historian Charles Wolfe noted in his The Grand Ole Opry Early Years 1925-35, “In fact, Judge Hay reported that Uncle Joe’s ‘heart would be almost broken each week because we would not permit him to play selections from the classics and light classics, which he did very well...’ Alcyone Bate recalled that Uncle Joe liked to play Italian waltzes with Shriver’s accordion backing him up, and on more than one occasion composed beautiful waltzes.”10

“’Blind Joe,’ plays everything from grand opera arias to the homelier melodies of break-downs. Blind since infancy, all of the power diverted from his sight seems to have gone into his touch and hearing for once having heard the most intricate of the classics he can reproduce its notes to what artists and critics call perfection. ‘Sometimes I cannot sleep for the music that comes to me,’” Joe said, in a 1927 interview with the Nashville Tennessean.11

Joe made his official Grand Old Opry debut on June 30, 1928, appearing as Uncle Joe Mangum billed with Deford Baily, Dr. Humphrey Bates and His Possum Hunters, and more. Before long he had become an Opry regular, but Mangrum was no rookie to Nashville. He had been performing in the city for years and in 1899 the Nashville Banner referred to him as the “Wizard of the Violin.” 12

But later in life he found new stardom in the upcoming Music City. He and Mary resided in a one room apartment at 143 6th Avenue North in Nashville and made friends with violin maker, John Rook. Despite his newfound fame, times were hard. Mary was robbed in 1931, and the robbers took all the couple's money. Luckily, they still had Joe’s reportedly 256-year-old violin which he continued to perform on at the Opry, churches, house parties, and nearly any place that would hire him.13

In a 1929 article titled, “WSM’s ‘Grand Old Opry’ Is a Success,” Paragould Soliphone author Israel Klein noted, “Uncle Joe Mangrum, almost 80 and blind, has been playin the fiddle for 70 years and still comes up here occasionally to give us a tune at the mike. Fred Schreiber (sic), also blind, plays the accordion with him. Uncle Joe has written pieces of his own. ‘Among Stars’ is one of them and a favorite with the fans.”14

“By 1931, he was one of the Opry's most popular performers and was on every week," Fayfare noted. “Fred Shriver, who was paired with Mangrum and played the accordion was an excellent player, according to reports. But the problem was that Fred and George Hay did not see eye to eye as to what kind of music should be played on the Opry and Hay would not allow Mangrum and Shriver to play some of their numbers.”15

In a 1976 interview with Rube Elrod, provided by the Kentucky Oral History Commission, Elrod notes that he learned a lot from Mangrum, playing with him in downtown Paducah as a child. He states that “Uncle Joe” often played on the streets of downtown and credited him as being a major influence on his playing style, especially the numbers “Molly Darlin,” “Fisher’s Hornpipe,” and “Mockingbird.” He goes onto to say that “He could play some deep notes!”16

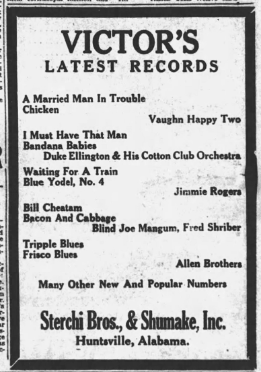

According to the Discography of American Historical Recordings, Mangrum and Fred Shivers recorded 5 songs for Victor in Nashville, TN, on October 6, 1928. While three of them, “Mammoth Cave Waltz,” “the Rose Waltz,” and “Cradle Song,” were never released, we do have the great opportunity to hear, “Bill Cheatam,” and “Bacon and Cabbage,” as provided here.17

Mangrum made his final Opry appearance on January 9, 1932. Less than a week later, Joe passed away on January 13, 1932, in Nashville, TN, 6 years to the day of winning the Old Fiddlers Contest. He had suffered a heart attack the previous day. 18

“He was the first of the early Opry stars to die while still a part of the show and the Opry did a tribute to him on the following Saturday night's show,” said Fayfare19

Joe Mangrum was a forefather to the region's musical history, both classical and country. While his passing was reported nationwide, time easily overlooks the past. With the Grand Old Opry celebrating 100 years, we remember this west Kentucky/Tennessee fiddler who once called Paducah home.

To learn more about Joe Mangrum and other Jackson Purchase musicians, please visit us in the Local and Family History Room at the McCracken County Public Library.

- Nathan Lynn

“Let the world move on I've got a world of my own.” - Joe Mangrum20

Citation

1 Tennessee State Library and Archives; Nashville, Tennessee; Tennessee Death Records, 1908-1958; Roll Number: 1, Ancestry.com. Tennessee, U.S., Death Records, 1908-1965 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011, Tennessee City Death Records Nashville, Knoxville, Chattanooga, Memphis 1848-1907. Nashville, Tennessee: Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Wolfe, Charles K. Kentucky Country. The University Press of Kentucky, 1996.

2 “Fulton.” Paducah Daily News Democrat, September 3, 1907, Vol. 40 No. 235 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/501601978/?match=1&terms=%22Joe%20Mangrum%22.

“In the Round-up.” Paducah Sun, August 31, 1912, Vol. 46 No. 197 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/502179244/.

“Amusements .” The Montgomery Advertiser, May 18, 1909, Vol. 80 No. 138 edition. https://www.newspapers.com/image/412794924/ .

“Local Notes.” Semi-Weekly West Tennessee Whig. February 14, 1885. https://www.newspapers.com/image/589116754/?match=1&clipping_id=new.

3 “‘Uncle Joe’ Mangum, Blind Violinist, A Musical Genius.” The Nashville Banner, April 13, 1930. https://www.newspapers.com/image/605079712/?match=1&terms=Blind%20Joe%20Mangum%20Chicago%20violin.

4 “Joe Mangrum, 79, Blind Violinist Died in Nashville.” The Mayfield Messenger, January 14, 1932, Vol. 30 No. 232 edition. https://www.newspapers.com/image/1090595441/?match=1&terms=Blind%20Joe%20Mangrum.

Fayfare, Byron. Thoughts on the 2011 Hall of Fame Class, March 7, 2011. https://fayfare.blogspot.com/2011/03/thoughts-on-2011-hall-of-fame-class.html.

5 The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Card Records of Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, ca. 1879-ca. 1903; Record Group: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General; Record Group Number: 92; Series Number: M1845

Ancestry.com. U.S., Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, 1861-1904 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

“From Other Counties.” Nashville Banner, August 28, 1889, Vol. 4 No. 127 edition. https://www.newspapers.com/image/603626347/?terms=Blind%20Joe%20Mangrum.

Fold3, US, Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Tennessee, 1861-1865 (https://www.fold3.com/publication/696/us-civil-war-service-records-cmsr-union-tennessee-1861-1865 : accessed Mar 18, 2025), database and images, https://www.fold3.com/publication/696/us-civil-war-service-records-cmsr-union-tennessee-1861-1865

“Joe Mangrum of Dresden...” The Memphis Commercial, June 13, 1891, Vol 3 edition. https://www.newspapers.com/image/585859665/.

6 Abbott, Lynn, and Doug Seroff. Ragged but Right Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

7 “Blind Player.” The Knoxville Journal, January 14, 1932. https://www.newspapers.com/image/586431965/?match=1&terms=Joe%20Mangum.

“‘Uncle Joe’ Mangum, Blind Violinist, A Musical Genius.”

Gilchrist, Annie Somers. The Night-Rider’s Daughter. Nashville, TN: Marshall and Bruce Company, 1910.

8 “‘Blind Joe’ To Marry.” Mayfield Messenger, October 18, 1915. https://www.newspapers.com/image/1017236513/?match=1&terms=%22Blind%20Joe%20Mangum%22.

9 “Blind Joe’s Music Pleases Radio Fans Far Away.” Paducah Sun, December 9, 1922. https://www.citationmachine.net/chicago/cite-a-newspaper/custom.

“Blind Joe Mangum Wins First Place in Fiddlers Meet.” The Paducah Sun, January 14, 1926. https://www.newspapers.com/image/503413789/?match=1&clipping_id=new.

“Want Blind Joe to Broadcast.” Paducah Sun January 15, 1926, Vol. 29 No. 11 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/502523531/ .

“Fiddling Trio at Foreman Company.” Paducah Sun January 16, 1926, Vol. 29 No. 12 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/502523579/ .

“Two Old and One Young Fiddler.” Paducah Sun January 17, 1926, Vol. 29 No. 13 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/502523611/?match=1&clipping_id=new.

10 “Blind Joe Mangrum is booked...” Paducah Weekly Sun, April 28, 1909, Vol. 25 No. 101 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/501424949/

“Amusements” Paducah Sun, September 1, 1913, Vol. 36 No. 208 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/503746667/ .

“Blind Joe Wants to do His Best” Paducah Sun, June 16, 1918, Vol. 52 No. 144 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/503746667/ .

“Blind Joes Music Pleases Radio Fans Far Away” Paducah Sun, December 9, 1922, Vol. 45 No. 294 edition. https://paducahsun.newspapers.com/image/503772634/?match=1&clipping_id=new .

“‘Blind Joe’ Mangum, Once Known Far and Wide as Violinist, Here: Ready to Play Again at 75; Talks of Days When Taylor Played.” The Tennessean. February 14, 1927. https://www.newspapers.com/image/178801908/?match=1&clipping_id=new.

11 Wolfe, Charles K. The Grand Ole Opry: The Early Years, 1925-1935. London, England: Old Time Music, 1975.

12 “‘Blind Joe’ Mangum, Once Known Far and Wide as Violinist, Here: Ready to Play Again at 75; Talks of Days When Taylor Played.” The Tennessean. February 14, 1927. https://www.newspapers.com/image/178801908/?match=1&clipping_id=new.

13“Nashville Radio.” The Tennessean. June 30, 1928, Vol. 23 edition, sec. No. 50. https://www.newspapers.com/image/181176460/.

Roland, Tom. Rolandnote.com: The Ultimate Country Music Database. Accessed March 18, 2025. https://www.rolandnote.com/people/timeline/Uncle+Joe+Mangrum.

“A Benefit Performance.” Nashville Banner, May 13, 1899. https://www.newspapers.com/image/603635564/?match=1&terms=%22Blind%20Joe%20Mangum%22.

14 “‘Uncle Joe’ Mangum, Blind Violinist, A Musical Genius.”

West, J. W. “Tuning In.” Nashville Banner, February 9, 1931. https://www.newspapers.com/image/605243341/?match=1&terms=Chicago%20opera%20blind%20joe%20mangum.

“‘Uncle Joe’ Mangum, Blind Violinist, A Musical Genius.” The Nashville Banner, April 13, 1930. https://www.newspapers.com/image/605079712/?match=1&terms=Blind%20Joe%20Mangum%20Chicago%20violin.

15 “WSM’s ‘Grand Old Opry’ Is a Success.” Paragould Soliphone. June 28, 1929, Vol. 28 edition, sec. No. 71. https://www.newspapers.com/image/1101768675/.

16 “McCracken County, Kentucky, Marriage Records.” Paducah, KY: McCracken County Clerks Office, n.d.

“Joe Mangrum, 79, Blind Violinist Died in Nashville.”

Fayfare, Byron. Thoughts on the 2011 Hall of Fame Class, March 7, 2011. https://fayfare.blogspot.com/2011/03/thoughts-on-2011-hall-of-fame-class.html.

17 Rube Elrod and Everett Cummins, interview by John Marshall, July 6, 1978, 1976OH04.12b, Kentucky Oral History Commission, Frankfort, KY.

18 “Blind Joe Mangrum.” Discography of American Historical Recordings. Accessed March 18, 2025. https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/100553/Mangrum_Blind_Joe.

19 Roland

Tennessee State Library and Archives; Nashville, Tennessee

20 Fayfare

21 “‘Uncle Joe’ Mangum, Blind Violinist, A Musical Genius.” The Nashville Banner, April 13, 1930. https://www.newspapers.com/image/605079712/?match=1&terms=Blind%20Joe%20Mangum%20Chicago%20violin.